The longer I help Christian organizations with hiring and succession planning, the more convinced I am that there are no cookie-cutter solutions to succession. I tell our new team members, we’ve done 1,500 searches, and if you’ve seen one church, you’ve seen one church. No two are the same. Every opportunity is unique. If you’re looking for a cookie-cutter, leave this article now, and if anyone tells you they have one, run now.

That being said, certain predictions can be made about how succession will work best at your church. Often, the succession style of a church resembles the culture of that church, and church culture is driven by the decisions of its leaders. Every congregation is classified as one of four different leadership styles.

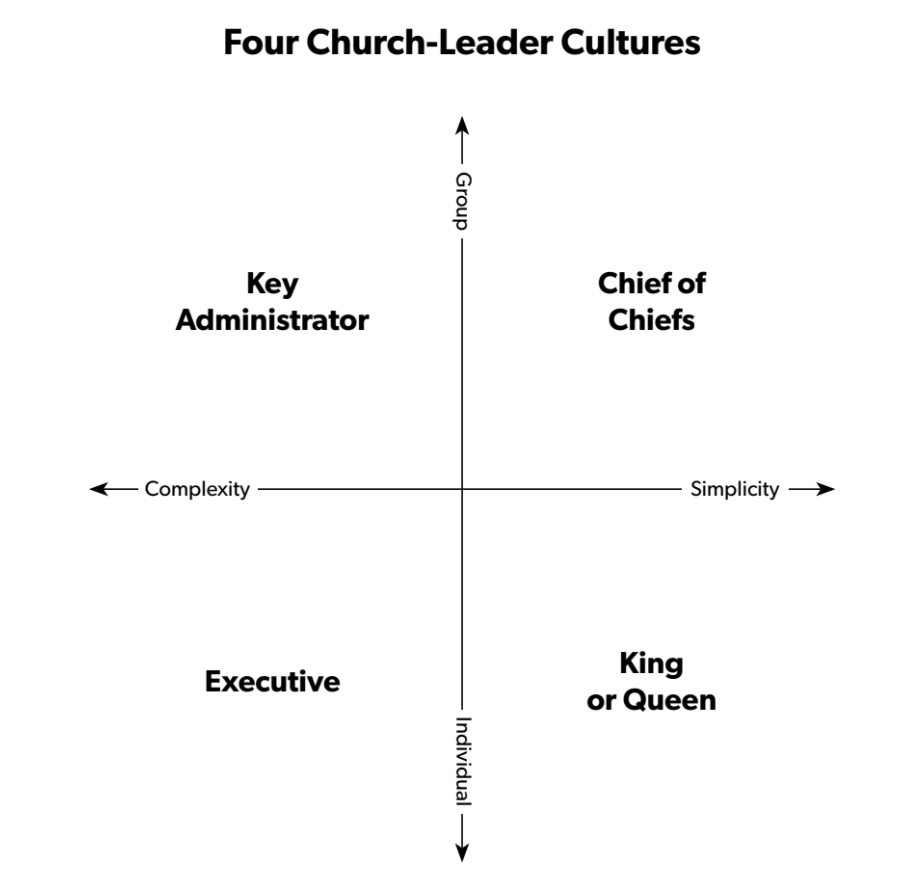

This chart was taken from chapter 7 of Next: Pastoral Succession That Works from the chapter, “Four Church Cultures, Four Succession Titles,” on Page 113.

- Left to right (x-axis) looks at the level of a church’s programming that directly involves the church’s senior leadership. This moves from complex (left) to apparent simplicity (right), depending on how the church’s programs are structured and supervised.

- Top to bottom (y-axis) explores the location of power and decision-making. This moves from group-based (top) to individual-based (bottom), depending on the level of teams, boards, committees, and systems that must work together to keep the church moving forward.

Every church can fit somewhere on this spectrum. Churches in each quadrant tend to handle decisions around succession in dramatically different ways. Church leadership teams can use this model to understand how their church should understand and develop succession pathways for their unique situation. To better illustrate how each of these pathways plays out, here are real stories from churches that fall into one of each of the quadrants.

1. Senior Pastor as Key Administrator

When Jim Henry became pastor of First Baptist Church in Orlando, Florida in 1978, one of the hats he took on was that of chief administrator. He says the church was led by a “type of executive committee made up of laity who led or served in various facets of the church’s ministry. They met on a monthly basis for reports and recommendations.”1 Over the years, the church grew and became more organizationally complex. It now conducts congregational votes only “on calling of ordained pastors, budget, financial matters that pertain to borrowing over $500,000, and major building programs.”2

Twenty-eight years later, when Jim Henry resigned and moved into various semi-retirement ministries, he was not the one to choose his successor. Instead, consistent with widespread Southern Baptist pattern, a lay-led search team found the next pastor, and then the congregation voted on him. The congregation didn’t treat Jim as a king when it came to succession; that power remained in a group (a deacon-commissioned search team to initiate the contact, interview, and recommend) and in the congregation (to vote). Thus, in keeping with the figure above, this succession model blends organizational complexity with group-based decision-making.

2. Senior Pastor as Executive

Dave Burns, founding pastor of Hillside Community Church in Alta Loma, California, was retiring. Although he had been there thirty-two years, the power resided with the elders to identify and call the next pastor. Vanderbloemen conducted the search for his replacement and saw the model at work firsthand. Dave was not present for many of the meetings, the laity ran the process smoothly, and thus far the succession has been a good one. Dave’s experience fits the “Executive” quadrant of the figure. His church demonstrates high complexity in the amount of programming directly involving the church’s senior leadership while being more individual in terms of the level of teams, boards, committees, and systems that must work together. Almost all the “seeker” churches fit here, especially those that are now second generation—led not by the founding pastor but by his or her successor.

3. Senior Pastor as Chief of Chiefs

In the “chief of chiefs” model, power is in a small group of chiefs. Each one not only runs an area of the church but has prominence over other pastors and staff. In churches like this, the board often plays a prominent role. Many times a number of staff are elders. It is common in churches that match this model for almost half the governing board to be staff. Thus, in keeping with the figure above, this succession model blends programmatic simplicity with group-based decision-making.

A few of the administrative models morph into a version of “chief of chiefs” as well. The senior pastor is often the spokesperson but, because of their committee structures and reporting structures, the other pastors have wide latitude and authority. Many mainline churches fit here as well given the framework that “you can’t fire me; only the session/personnel committee can.”

4. Senior Pastor as Head of “Royal Household”

Much like small businesses, family systems abound where a relative is assumed to be the hands-down first choice among any potential candidates.

At age fifty-seven, Billy Joe Daugherty unexpectedly died. He had served as founding pastor of Victory Christian Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He was also the founder of Victory Christian School, Victory Bible Institute, and Victory World Missions Training Center. One month later, Billy Joe’s widow, Sharon Daugherty, was elected president of the Victory Christian Center Corporation. The Daughertys have two daughters and two sons. All four children, along with their spouses, stepped up in the first year after their father died, each shouldering key administrative and pastoral responsibilities for their mother. In 2014, son Paul and his wife, Ashley, became lead pastors of the church. The model they represent is closest to that of a family business or “royal court,” where it is expected that spouses and children will be the next to take over.

But the “Royal Household” model does not always have to occur within a family. A non-family example is J. Don George, who was the longtime pastor at Calvary Church, an Assemblies of God congregation in Irving, Texas. In 2011 he passed the leadership mantle to a young protégé, Ben Dailey, to whom he is not related. By the end of Ben’s first year a third of the staff was new, most close to Ben’s age, representing a very different operation style than J. Don’s. Yet because the outgoing pastor blessed all those changes, Ben remains as pastor—and to both pastors’ delight, the church has grown significantly since the pastoral transition.

I hope that by identifying these four models of leadership, pastors and boards can know themselves a bit better before undertaking the unique process of pastoral transition. However, since churches can lay anywhere in this spectrum, it’s important not to try to force one style to fit. Most likely, you’re a combination of these styles. If you’re thinking about succession planning, and need help knowing what steps to take next, check out chapter 7 of my book Next: Pastoral Succession That Works, where I provide a roadmap for navigating this sometimes challenging time in life. You can also contact my team at Vanderbloemen if you’re ready to start the conversation about succession planning on your team.

1Jim Henry, “Pastoral Reflections on Baptist Polity in the Local Church,” Journal for

Baptist Theology and Ministry 3:1 (Spring 2005), 107. Available online at http://www.baptist

center.net/journals/JBTM_3-1_Spring_2005_07_Pastoral_Reflections_on_Baptist_Polity.pdf.

2 Ibid, 108.